Moncrieff: 81-93; Sturrock: 63-72

by Dennis Abrams

Another reason Marcel is irritated by the Turkish Ambassadress: At the Duchesse de Guermantes’ house, she had spoken disparagingly of the Princesse de Guermantes, remarking that “She is stupid. No, she’s not so beautiful as all that. That reputation is usurped. Anyhow…I find her extremely antipathetic.” But now, armed with an invitation to the Princessess’ she is singing a different tune, “‘Ah! What a delightful woman the Princess is! What a superior person! I feel sure that, if I were a man,’ she went on, with a trace of oriental servility and sensuality, ‘I would give my life for that heavenly creature,'” adding that there is no comparison between her and her cousin the Duchess. The reason for her change of heart? “Our judgment remains uncertain: the withholding or bestowal of an invitation determines it.” “The real stars of society are tired of appearing there…but women like the Ottoman Ambassadress, a newcomer to society, are never weary of shining there, and, so to speak everywhere at once. They are of value at entertainments of the sort known as receptions or routs, to which they would let themselves be dragged from their deathbeds rather than miss one.” The ability of the Duchesse de Guermantes to make her eyes “sparkle with a flame of wit only when she had to greet some friend or other,” and at the party, having decided that it “would be tiring to have to switch off the light at each,” makes “sure that her eyes were sparkling no less brightly than her other jewels.” The Duchess assures Marcel that of course she knew he would be invited. Marcel’s success climbing the social ladder and his mastery of the social arts. Marcel hears M. de Vaugoubert’s voice, and recognizes it as being like that of Charlus, the voice of an invert. A conversation between Charlus and Vaugoubert, in which Charlus informs him, always disparagingly, of the large numbers of inverts surrounding him, up to and including King Theodosius. “…he has all the little tricks. He has that ‘my dear’ manner, which I detest more than anything in the world. I should never dare to be seen walking in the street with him.” Mme d’Amoncourt, playing her literary connections for all they’re worth, informs the Duchesse that she has a letter in which D’Annunzio says that he saw her from a box in the theater, and “he says that he never saw anything so lovely. He would give his life for ten minutes’ conversation with you,” and goes on to add that she has “the manuscripts of three of Ibsen’s plays, which he sent to me by his old attendant. I shall keep one and give you the other two.” The azure eyes of the Duchesse de Guermantes. The people: Jews, Bonapartists, and Republicans who interested the Duchess but are not allowed to visit the Princesse de Guermantes because of the Prince’s views. The exception the Prince makes for Swann, because he has convinced himself he is actually the grandson of the Duc de Berry and fully gentile. The Duchesse praises the splendors of her cousin’s ‘palace” while adding that she preferred her own “humble den,” adding that “I should die of misery if I had to stay and sleep in rooms that have witnessed so many historic events. It would give me the feeling of having been left behind after closing-time, forgotten, in the Chateau of Blois, or Fontainebleau, or even in the Louvre, with no antidote to my depression except to tell myself that I was in the room in which Mondaldeschi was murdered. As a sedative, that is not good enough.” The arrival of Mme de Saint-Euverte.”

—-

What a cornucopia of riches this section was! One hardly knows where to begin…the Ambassadress…the conversation between Charlus and Vaugobert with the references to the “young secretaries…not chosen blindfold,” and the Racine choruses…the Duke’s concern that Ibsen and D’Annunzio might still be alive and showing up at his house any moment…but I was particularly struck by the lessons learned by Marcel on how to act with the aristocracy, and the Guermantes in particular.

“I was beginning to learn the exact value of the language, spoken or mute, of aristocratic affability, an affability that is happy to shed balm upon the sense of inferiority of those towards whom it is directed, though not to the point of dispelling that inferiority, for in that it case it would no longer have any raison d’etre. ‘But you are our equal, if not our superior,’ the Guermantes seemed, in all their actions to be saying; and they said it in the nicest way imaginable, in order to be loved and admired, but not to be believed; that one should discern the fictitious character of this affability was what they called being well-bred; to suppose it to be genuine, a sign of ill breeding.”

And of course there’s the scene in which Marcel knows enough to ignore the Duke’s signals to approach him and the Queen of England. By this stage, Marcel knows enough to give a deep bow and walk quickly in the opposite direction, forever earning the admiration of both the Duke and the Duchesse. “They never ceased to find in that bow every possible merit, without however mentioning the one which had seemed the most precious of all, to wit that it had been tactful; nor did they cease to pay me compliments which I understood to be even less a reward for the past than a hint for the future…”

—

And, finally, a bit more from Sean Wolitz’s look at the real French aristocracy in The Proustian Community:

“To live outside the Faubourg, though imitating it, must have been frustrating, not unlike kissing a woman through a veil. but eventually the bourgeois used his economic means to penetrate first the impoverished noble society and eventually, by social osmosis, the inner Faubourg. the Lebaudy family, the great sugar merchants, did this, as did the Wendels and the Schneiders, the Carnegies of France; and the French symbol of supreme wealth, the Rothschilds, who even received an Austrian title, though Jewish, and whose daughers in 1900 were married to such distinguished noblemen as the Prince de Wagram and the Duc de Gramont. Marriage remained the assured way to obtain and secure entrance.

Besides rich Jewish maidens who became ennobled through marriage, there were American girls such as Anna Gould, who married Comte Boni de Castellane, and Mattie Mitchell, who married the Duc de la Rochefoucauld; they offered rich dowries and were absorbed quickly. (The Princesse de Monaco nee Kelly continues the tradition in our time.) the name of the families was continued, but the origins of the bearer are radically different.

Proust’s treatment of high society would be in fact a study more of the bearer and how he or she rose to the Faubourg than of the history or mystique of the title. the great truth which Proust would reveal about society is that it constantly changes within each strata; as an audience does every night in a theater.

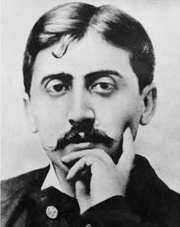

Young Proust, on the fringes of high society, held several advantages besides the necessary wealth: intelligence, urbanity, artistic inclinations, and the exoticism of being half Jewish. He began the climb early. Through his lycee friend Jacques Bizet, he entered his first literary salon, that of his friend’s mother, Mme Straus — a rather good beginning. This salon mixed artists with artistically inclined nobles. In 1890 he met Gaston de Caillavet, who took him to his mother, Mme Arman de Caillavet, who charmed the leading writer Anatole France to her gilded cage and thus created the leading bourgeois salon of the Belle Epoque. Through this salon Proust received invitations to other literary bourgeois salons and met enlightened nobles. He was able to meet the Empire nobles in the salon of the Princesse Mathilde, whose salon was not difficult to enter. In 1893, Proust met the Comte de Montesquiou at Madeline Lemaire’s salon. According to Jacques-Emile Blanche, Proust’s friend and portraitist, Proust had not really circulated among the ‘gratin’ of the Faubourg until Montesquiou made it possible.”

—

The Weekend’s Reading: (Since it’s a holiday weekend, I won’t be posting a synopsis and notes until Monday night/Tuesday morning, which should give anyone who might be behind a chance to catch up.)

Moncrieff: Page 93 “As a matter of fact, Mme de Saint-Euverte had come this evening…” through Page 123 “I was just crossing the room to speak to Swann when unfortunately a hand fell upon my shoulder.”

Sturrock: Page 72 “In point of fact, Mme de Saint-Euverte had come there that evening…” through Page 93 “I was about to cross the smoking room to talk to Swann when, unfortunately, a hand came down on my shoulder.”

Enjoy. And enjoy your weekend.